Italian researchers have demonstrated the long term effectiveness of using stem cells to cure corneal blindness. From 1998 to 2006 the team, headed by Graziella Pellegrini at the University of Modena, performed 125 stem cell procedures on 112 patients, all who had lost partial or complete vision due to chemical or thermal burns. Stem cells were taken from the limbus in the patient’s own eye, cultured, and then grafted back on the eye. As recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the grafts had a success rate of 76.6% – leading to restored or improved vision. Better still, the positive results have lasted – one patient has been followed for more than 10 years and still has healthy vision. That’s remarkable. This work represents a real group of people who have already had their lives radically changed through stem cell treatments. More patients all around the world may see benefits from this technique soon.

Using grafts of stem cells to treat corneal blindness isn’t a new idea. Pellegrini and collaborators like Michele De Luca, were pioneering different versions of the technique back in 1997. We’ve seen related approaches to restoring damaged corneas, most notably in New South Whales. This report in NEJM, however, has something that few (if any) have presented before: a relatively large sample set that shows positive results verified over the long-term. Ten years for a successful stem cell transplant? Outside of bone marrow grafts, almost no one has that kind of follow-up history for stem cells. It’s a great sign that what Pellegrini and colleagues are doing is a viable long term cure for corneal blindness.

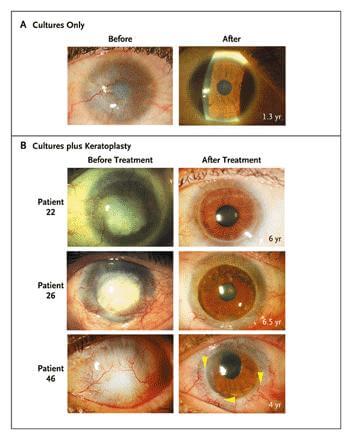

These before and after pictures are astounding. The top example required no further surgery to correct vision, but the others need keratoplasty.Notice the small notations in the right picture that indicate how long after treatment the images were taken. The arrows in the last row highlight that blood vessels no longer intrude onto the cornea.

The NEJM article also describes an important development in being able to predict the success of a stem cell treatment. Many of the patients in the study had mild to severe limbal damage, limiting the amount of healthy stem cells that could be harvested and cultured. Pellegrini’s team monitored levels of p63 transcription factor in the stem cells they harvested from patients. When the number of ‘p63-bright’ cells was greater than 3%, the success rate of the eventual transplant ended up around 78%. When it was less than 3%, the outcome was successful only 11% of the time. This work demonstrates that very little of the limbus need remain healthy for the stem cell transplant to still work. Using p63 levels as a metric could allow doctors to present patients with a better idea if a corneal stem cell transplant would be successful. It also hints that p63 transcription factor could be augmented or controlled in some way to improve stem cell therapies of this kind.

Amidst all the success in this recent report, we must also face some serious limitations of the work. First, these stem cell treatments were only used for corneal blindness. Not only that, but a very specific cause of corneal blindness – burns. Chemical and thermal burns can cause a wide variety of injuries to the eye, but often leave all parts of the inner eye and optic nerve functioning. Some patients retain some form of (very limited) vision. Also, because of the nature of the causes of these injuries, more than 78% of the 112 patients were men. While thousands lose their vision to chemical accidents every year, there’s a huge number of people with vision problems related to other corneal damage, retinal damage, and nerve damage that are unlikely to benefit from this technique in stem cell transplantation.

It’s also important to note that while the study followed one patient for more than 10 years, the average follow-up was closer to three years (with large variation). That’s still pretty good, but it’s not the same as saying that all 112 patients were tracked for a decade. As always, smaller data sets mean data has to be taken with a grain of salt.

Finally, I should point out that the term ‘positive results’ covers a wide range of changes in vision. A few went from seeing nothing to having restored vision. Some patients went from only being able to see the vague outline of fingers to actually being able to read and determine fine shapes. Others saw more modest improvements, and 24% failed to benefit. These changes didn’t happen overnight; they often took many weeks or more than a year to develop. About half of patients needed keratoplasty (reshaping of the cornea) to correct their vision, though that is a relatively simple procedure these days. Bottom line, it wasn’t like these patients got an injection of their own stem cells and could miraculously see the next day. Stem cells taken directly from their eyes had to be cultured and then grafted onto the cornea, and there was a sustained period of follow-up and further medical care before doctors or patients knew how successful (if at all) the procedure would be.

Still, these results are real world examples of how stem cells are already treating a loss of vision. Pellegrini and her colleagues may be able to adapt their technique to treat other (more common) forms of corneal blindness with the same impressive outcomes. Their confirmation of the importance of p63 transcription factor could also prove helpful in the wider field of regenerative medicine. This work is another victory for stem cells and another step towards being able to regenerate or regrow every part of the human body. I’m deeply impressed.

[image credits: Rama et al NEJM 2010]

[source: Rama et al NEJM 2010]